There is a unique kind of logic within each human language. Studying a second language means learning to think in a way that is different from the patterns of thought in one’s first language. Western languages, such as English, French, German, and Spanish, tend to promote linear thought patterns. There is the expectation that each new idea adds more and more to preceding ideas resulting in a final product that is the culmination of everything that has come before. In other words, the most important conclusions come at the end of a chain of thought. Other languages have different logic. Years ago, I used to become frustrated with my Arab friends because they always seemed to dance around the main point without getting to it. Eventually, I realized that the Arabic language promoted a spiral logic that circled around the central idea drawing closer with each circle while still not directly stating the main point. (I believe, however, that this spiral logic of Arabic has changed somewhat in recent years as western logic has made inroads into Middle Eastern societies.) The concept of specific organizational structures being tied to specific languages is relevant to Christians because Hebrew organizational structure affects a person’s ability to understand the Bible. It is not enough to be able to read the word of God in our own language. It is also important to be aware that Hebrew has a special pattern of thought that is present throughout the scriptures. Theologians have labeled this pattern of communicating by the term “chiasm.”

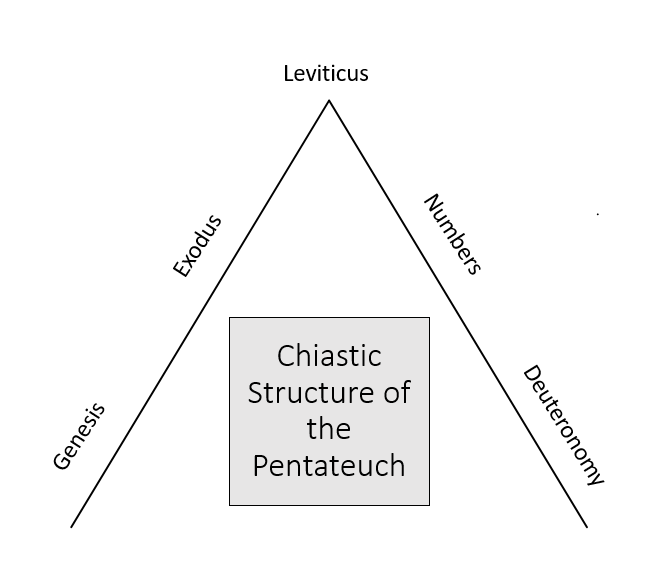

A chiasm has been compared to a mountain where there are corresponding points of information on each side (going up and down). The peak in the middle is the most important piece of information in the passage. Thus, in Hebrew logic the culminating point is in the middle of the argument rather than at the end. This can make a passage of scripture seem disjointed and repetitious for no reason to a western reader who is using western logic. However, as you start to get a feel for the chiastic structure of the Bible, new and exciting insights will open up for you. A diagram of the chiastic structure of Leviticus looks like this:

When I was first learning about chiasms, I had difficulty wrapping my mind around the significance of this kind of organization. I understood the idea in theory, but its importance and meaning simply would not compute. I eventually found that the best way for me to understand chiastic logic was to examine some chiasms that have been discovered in the Bible by various theologians. I wanted to share this experience with you, so I will give you some examples of chiasms from a book called The Inside Story Jonah by Jo Ann Davidson. My advice is to compare the letter and its prime as you read rather than reading up and down the mountain. For example, read A and A’ (A prime) at the same time. Then read B and B’ together. You will start to see the pattern and how the middle letter is the culminating idea.

If we compare A and A’, we see God making man from the dust of the ground and placing him in the garden contrasted with man being sent away from the garden and told to produce from the dust of the ground. Comparing B and B’ emphasizes how the relationships among creatures has changed from the unity of Genesis 2:18-25 to the enmity between the woman and serpent and the disharmony between the man and woman. C and C’ are both dialogues with three parts on the topic of eating from the tree. The chiastic structure shows that the heart of the story, the main idea, is the fall of Adam and Eve because of eating the fruit of the forbidden tree. All the other parts of the story revolve around this one act. The chiastic structure emphasizes how everything changes because of this singular choice.

Step 1 of the chiasm includes a covenant that God makes with Noah that he and his family will be safe during the flood in Genesis 6:18. In step 1’ God makes another covenant with Noah and all the creatures of the earth that there will never be another worldwide flood. Thus, the chiasm begins with covenant and ends with covenant. In steps 2 and 3, the animals enter the ark so that they will not die. More of the clean animals are saved than unclean animals. In steps 2’ and 3’, Noah is given permission to use the clean animals for food, and Noah sacrifices clean animals to God. Ironically, animals that have been saved from the flood waters are killed for sacrifice and food. Steps 5/6 and 5’/6’ contrast the flood rising and the flood abating. Thus, the climax of the story is when the flood crests and the ark rests. At that time, we are told that God remembered Noah. Of course, God had never forgotten Noah, so this central point is emphasizing God’s care the whole time. In other words, the most important idea in this story is that God did not leave Noah alone. The center of the chiasm emphasizes that God never forgot Noah before, during, or after the flood.

A and A’ are the introduction and epilogue. B and B’ are decrees from the king. C and C’ deal with the clash between Mordecai and Haman and Mordecai’s triumph. This leaves the night that the king could not sleep as the turning point of the story. However, this chiasm needs more sections than the simplistic diagram I have shown here because of the complexity of the chiastic structure found in the book of Esther. In addition to the information provided in the chiasm here, there are three banquets before the turning point and three feasts after. Key words appear the same number of times before and after the turning point. In addition, there are references to the royal chronicles at the beginning, at the turning point and at the end.

The parable of the prodigal son starts with inheritance and ends with inheritance. In both A and A’ the father’s generosity with his sons is displayed. In B, one son goes out and behaves badly. In B’ one son behaves badly by refusing to go in. In C and C’ the father’s servants are part of the story. In C, the remembrance of how well the servants are treated draws the son away from death. In C’, the servants are part of the celebration because the son is alive and back in the household. D and D’ both focus on the repentance of the son. The most important message in this story is the father running out to meet his prodigal son and treating him with compassion. The message of the Father’s love has always held meaning for me, but seeing its place in the chiastic structure emphasizes that Jesus Himself wanted us all to focus on the father running to welcome the sinner back into the household. Jesus wanted us to understand that we are to behold the Father’s extreme love before focusing on the sons’ bad behavior or even upon the prodigal’s repentance. It is the Father and his love that is the central message of the story, not the sons’ lack of love. In other words, it is our Father’s extreme love for us and not our own sinfulness that we need to always keep in mind.

Chiasms are found throughout both the Old and New Testaments. They range in magnitude from the organization of the five books of Moses to the single verse of Jonah 1:3. God’s speech in Exodus 6:2-8 is chiastic. Other chiasms include the entire book of Hebrews and the messages to the seven churches of Revelation. I confess that I have not advanced enough in my understanding of the Bible to pick out these chiastic structures without help yet, but once they are pointed out to me, the structure seems obvious. Now that I understand this kind of organization better, repetitions of information no longer seem meaningless and unnecessary. Instead, they are an integral part of the flow of information and become signposts pointing to the central message that God wants us to understand.